Dutch - French ties in 17th century map production

In the first half of the 17th century, the publishing house Hondius / Janssonius / Blaeu dominated map publishing in Europe. It is known that, at the beginning of the 17th century, French publishers traveled to Amsterdam to buy maps unavailable in Paris.

The Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Danckerts the elder made selling trips to Paris and was associated with Melchior Tavernier, who

became at the beginning of the 16th century the most important publisher in

Paris. The Dutch strongly influenced him and must have visited Amsterdam regularly. In 1638, he paid 500 pounds to H. Hondius and 1,000 pounds to Willem Blaeu, most likely for maps he sold at the depot. (Fleury, Archives nationales, documents du minutier, etc. (Paris 969), vol. I, p.652).

J.Boisseau copied after or used maps by H.Hondius, J.Jansson, W.Blaeu and C.Danckerts in his "Theatre de Gaules" from 1642. (Reference: Imago Mundi 32. M.Pastoureau, Imago Mundi 32)

In France, the pioneer in making world atlases was Nicolas Sanson d’Abbeville and his partner, the publisher Pierre Mariette (1603-1657). It is not before 1658 that Mariette produced a folio world atlas with an engraved title page, Cartes Generales de Toutes les Parties du Monde. The atlas is considered the first folio world atlas published in France. Between 1620 and 1658, a few folio world atlases were produced, all without title pages.

These atlases contain several maps originating from Amsterdam. Regional maps at that time not available in Paris are completed with Dutch maps, often produced by Jodoocus II and Henricus Hondius,

Johannes Janssonius and Cornelis Danckerts.

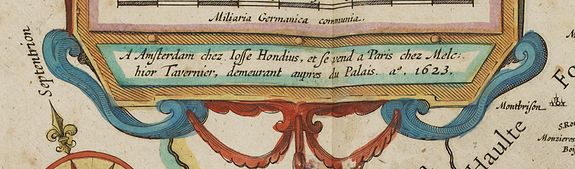

With the Frankfurter Buchmesse already established, Latin was the commonly used language for map titles and often text. As a matter of fact, the Amsterdam publisher Hondius produced a large number of French maps with a French title and even the publisher's address in French; "A Amsterdam chez Josse Hondius, et se vend a Paris chez Melchior Tavernier, demeurant aupres du Palais A° 1623". This map was found in the standard Dutch atlases (and in French composite atlases). These maps demonstrate the ties between Paris and Amsterdam at the beginning of the 17th century.

French publishers went to Amsterdam to buy those maps not available in Paris. Also, Dutch merchants visited Paris to sell their maps. Several joint ventures are known. The stock of Tavernier included a large number of

maps printed in Amsterdam by Jansson, Hondius, Blaeu, C. Danckerts.

Nicolas Sanson (1600-1667) was born in Abbeville, where, as a young man, he studied history, particularly of the ancient world. At the age of 18, he was said to have compiled his first map. After he moved to Paris the King appointed him 'Geographe Ordinaire du Roi', one of his duties being to tutor the King in geography.

Melchior Tavernier was Paris's most active publisher of prints and maps at the beginning of the 17th

century. Sanson published his first separate map and atlas of France and Europe with Tavernier.

For unexplained reasons, Melchior Tavernier retired from trade in 1644. He sold most of his stock of copperplates, prints, maps, architecture books, blank paper, and printing press to Pierre Mariette for 11,200 pounds.

Maps by Cornelis Danckerts II (1603-1656) are also often found in French composite atlases. Danckerts II He started his business in Amsterdam in 1633 and was "Papiere const en Caeren verkooper". He was associated with Tavernier.

The Dutch maps found in the French early composite atlases usually lack text on the verso and are printed on thinner paper, most likely to match the paper quality used by the French publishers. The Amsterdam publishers typically used thick, high-quality paper and, after 1635, printed the text on the verso of their maps.

The early Dutch maps, printed on thinner, often off-white paper and without text on the verso, are therefore typically intended for the Paris market. It was usual to print the text on the verso before the copperplate map. As the Paris publisher never printed text on the verso, they were able to keep a stock of Amsterdam-printed maps to assemble into their atlases.

Of the examples we have handled over our 42 years in the map trade, 90% of the paper has no watermark, unlike the French-printed maps in the same atlases, which most often have one.

In a few cases, the Dutch printed maps have a watermark; their origin is French. (A crowned single French Lily in a shield).